Images Courtesy of The Alternator

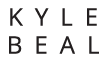

SCREEN TIME

2022

The Alternator, Kelowna BC

You can’t watch your own image and also look yourself in the eye // Shauna Thompson

a reflection on Kyle Beal’s Screen Time

Our current archeological record suggests that the earliest human-made mirrors were created approximately 8,000 years ago in southern Anatolia, or what is now south-central Turkey. These Neolithic mirrors, unearthed in the settlement of Çatalhöyük, are round or ovoid, approximately palm-sized, and were painstakingly crafted from obsidian, a deep black volcanic glass, with very finely polished, slightly convex surfaces. Remanent white material on the back sides of several examples was revealed to be lime plaster, and it is speculated that the mirrors were once embedded in interior walls, though most examples have actually been unearthed in burial sites (mostly those of women) as grave goods.[1] In the epochs following the ingenious creation of these objects, human cultures the world over devotedly formed mirrors from all kinds of materials: iron ore, copper, gold, bronze, silver, selenite, slate, haematite, magnetite, glass, and others. Explanations for the function of these significant, labour-intensive objects have ranged from aiding dress and makeup application, to a means of communication via signalling, to telling time, to illumination, to spiritual rituals and rites.[2] Ultimately, this familiar litany of uses is about knowledge, seeing and being seen, and a sustained history of humans striving to know themselves and their place in the world.

The Neolithic obsidian mirror—and its descendants—resonate formally across time to find a parallel in the handheld black mirrors we stare into every day. We are accustomed to the quotidian use and familiar existence of mirroring technologies in our lives, and psychologically this ubiquitous presence—both literal and figurative—symbolizes the Lacanian “possibility of self-awareness and self-contemplation embodied by the power of reflection.”[3] Our experience of being reflected is amplified via the mirroring affect of social networks, and many of us willingly (and sometimes with obsessive passion) embrace the role of becoming the authors of our digital identities, which subsequently forms and influences our self-concept. As Susan B. Barnes notes, the development of a clear self-concept acts “as kind of a shorthand approach by which the individual may symbolize and reduce his own vast complexity to workable and useable terms.”[4] Harkening back to Lacan’s Mirror Stage, a coherent self-concept is not hermetically developed; rather, it is fundamentally dependent on the existence of an external presence within a social and linguistic framework, that is, the presence of the Other.[5] What more powerful and wide-ranging tool do we have in the development of the self-concept than the omnipresent multidirectional reflection provided by our engagements with and through social media?

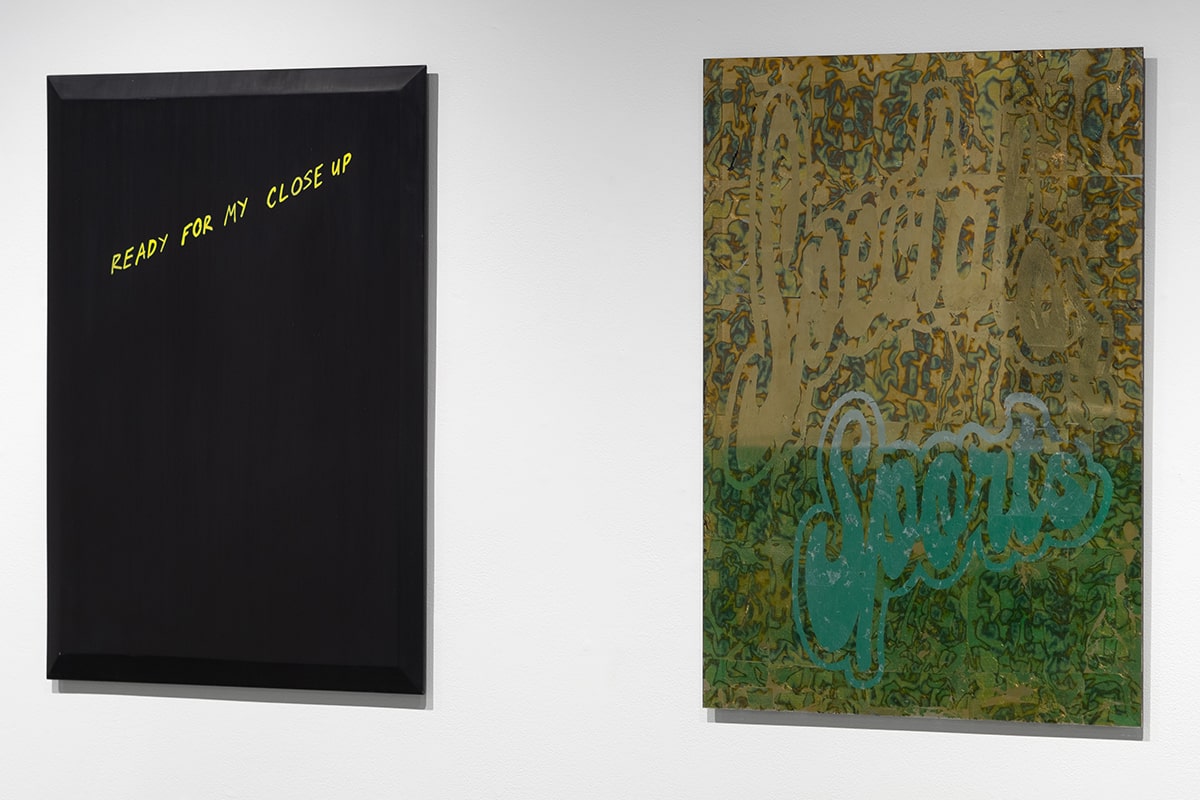

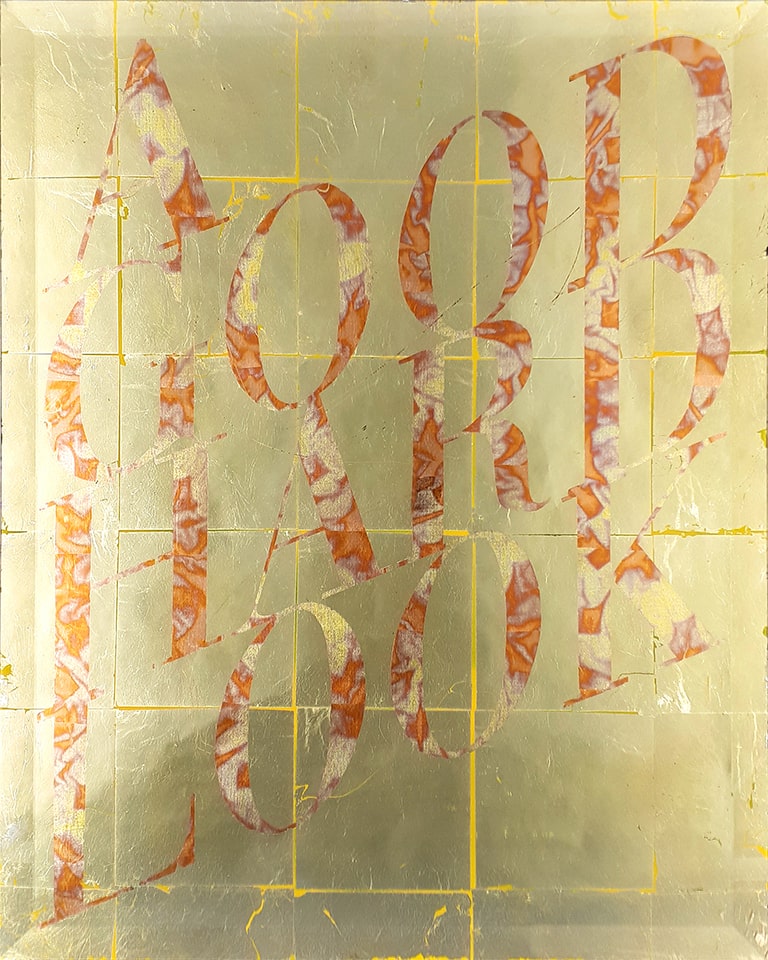

The resonance and importance of these identity-shaping mirrors—both analog and digital—serve as a starting point for Kyle Beal’s Screen Time. Beal’s sculptural works gesture to the complex dynamics of seeing and being seen, the two-way mirror of social media, the peep show of identity performance and self-perception, and also our ever-present preoccupation with materials and technologies that reflect ourselves to ourselves and to others.

Situated at the core of the exhibition is Green Room, a provisional-looking cube of green-tinted Plexiglas that references the site in a theatre or studio where performers wait while they are not engaged in a performance. Taking formal inspiration from Richard Serra’s One-Ton Prop (1969), the sculpture is tenuous and minimal, and though it is physically impenetrable, it is transparent and visually accessible. If this is a site for preparation or practice, it is an uncertain and vulnerable one.

Nearby is Mirror Stage, which takes the form of a small overturned crate, and calls to mind the provisional stage of a public street preacher or busker—a device used to “get up on one’s soapbox”—a literal platform for a possible performance. Here is the counterpart to the space of preparation of Green Room: a metaphorical stage upon which you are invited to stand and deliver your piece, or perhaps pontificate or grandstand, to an implied audience. The slats of the crate are aluminum polished to a chrome finish—promising to reflect both performer atop it as well as gathered spectators. The metal-leafed idiom emblazoned on the side of the crate is “Bottoms Up”; a toast to those gathered, or perhaps a portent of things to come once the performance has finished.

These sculptural works call to mind Erving Goffman’s influential proposition in The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (1956) that every human being performs roles in daily life via a series of social interactions, and identity is formed through that series of performances, which are enacted consistently over time (though the performance or roles we play change in response to exposure to different audiences—a different performance for the home, another for the office, and so on). In other words, our sense of self and identity are constructed by the roles we perform with repetition and continuity.[6] This definition can be extrapolated to include the way that we perform ourselves via social media platforms, the difference being that online is where the space of preparation and performance blur and the clear divide between private and public dissolves. As Abigail de Kosnik notes, in fact it is “the ongoing blending of front stage and backstage, the public posting online of one’s ostensibly private life, that constitutes a great deal of the appeal of social media performance; hence…in social media use, the metaphorical wall separating private and public is made of glass, transparent and meant to be seen through.”[7]

In the early 1970s Marshall McLuhan proposed the developing concept of “global theatre” in which “all can perform to all, in which no one is merely a spectator, but all are actors.”[8] In a sense, not only are we are all continually preparing and performing in a transparent green room; but we are spectating as well. This is not unlike the dynamics of a theatre space wherein participants of the event experience a sense of co-presence and a kind of self-reflexive feedback loop: audience members are immersed in the environment of the production, the performance of the actors, as well as the performance of their fellow audience members, and the actors are immersed in the production, their own performance, as well as the presence and response of the audience. For action to be meaningful, and for our selves to be seen, there must be a recognition and response.[9]

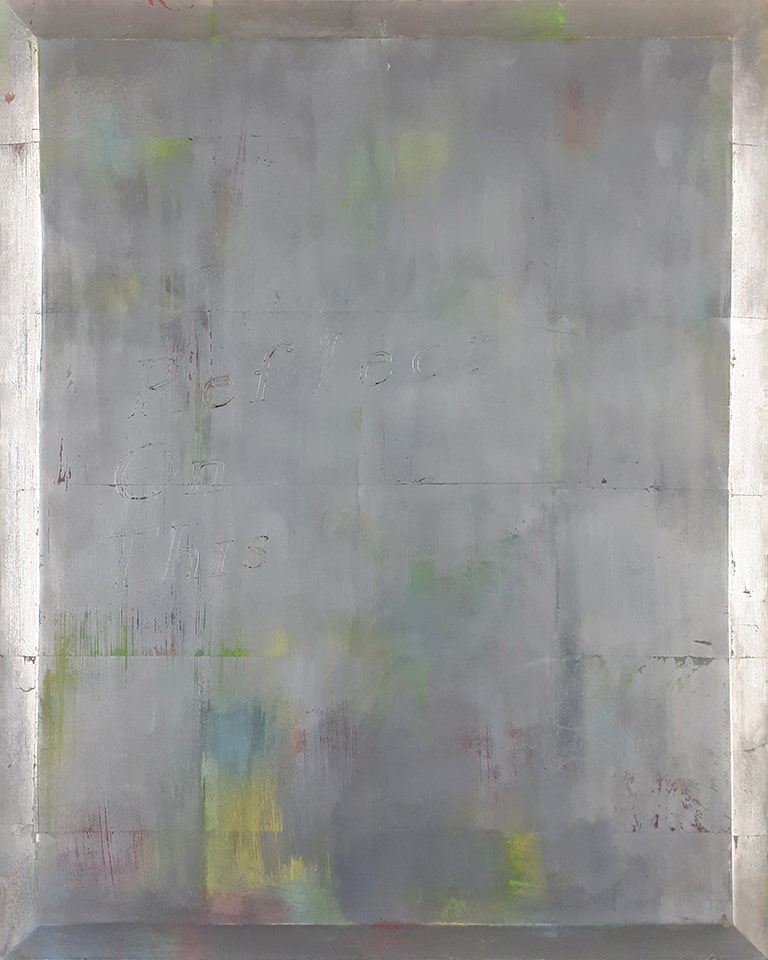

Starting in the 1960s, artists began experimenting with a shift in material exploration. Industrial materials, including Mylar, Plexiglas, powder coating, and metals, began to increasingly appear in works, and materials with reflective qualities fostered a preoccupation with surface and a sense of ambivalent physicality and depth. Reflective materials also, of course, made the viewers themselves—and their reactions and interactions—visible within the artwork.[10] Green Room’s formal connection Serra’s sculpture recalls the post-minimalist tendency to force the viewer to recognize and reckon with their own body in the context of the installation space and the work. In this installation, Beal complicates this by surrounding the viewer with a series of mirrored works in which, to varying degrees, they are confronted with iterations of their reflection, overlayed with text, such as “All Alone But With Everything,” “Almost Unrecognizable Reality,” “Feels Good to See Myself in This,” and “Feels Weird to See Myself in This.” Though made of different (or differently treated) reflective materials, these mirror works are presented in the same standardized format of a 30” x 24” rectangle, which somewhat replicates a sense of the uniform grid of an app like Instagram. The layering of text seems to allude to the powerful socio-linguistic phenomenon of the meme format—a kind of shared visual language that both the individual and the collective can relate to and see themselves within.

Through the omnipresence of mirroring technologies like smartphones and social media, contemporary art exhibitions have become a framework that offers viewers the opportunity to engage in the often-pleasurable process of developing and presenting a self-concept, and to fulfill the compelling need to be responded to and recognized. This framework also allows these viewers to observe and respond to the same actions taken by others. In this case, the formal qualities of the works in Screen Time, (as well as the exhibition text,) self-reflexively recognize these dynamics by acknowledging that viewers will inevitably take selfies within the installation. By producing a framework for documenting and sharing the self, Beal knowingly draws the exhibition itself into the ever-growing feedback loop of global performance.

[1] Josef Vit and Michael A. Rappenglück, “Looking Through a Telescope with an Obsidian Mirror.” Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry Vol. 16, No. 4 (2016): 11. http://maajournal.com/Issues/2016/Vol16-4/Full2.pdf

[2] James F. Vedder, “Grinding it Out,” Archeaology Magazine, April 2 2001, https://archive.archaeology.org/online/news/mirrors.html

[3] Vit and Rappenglück, “Looking Through a Telescope with an Obsidian Mirror,” 9. http://maajournal.com/Issues/2016/Vol16-4/Full2.pdf

[4] Susan B. Barnes. Online Connections: Internet Interpersonal Relationships. (Creskill, NJ: Hampton Press, 2001), 236-237.

[5] Jacques Lacan. “The Mirror Stage as Formative of the I Function as Revealed in Psychoanalytic Experience.” Jacques Lacan Écrits: The First Complete Editions in English. Bruce Fink, trans. (New York, NY: W. W. Norton, 2006), 75-81.

[6] Abigail De Kosnik, “Is Twitter a Stage?: Theories of Social Media Platforms as Performance Spaces.” in #identity: Hashtagging Race, Gender, Sexuality, and Nation, edited by Abigail De Kosnik and Keith P. Feldman, 21. University of Michigan Press, 2019. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvndv9md.5

[7] De Kosnik, “Is Twitter a Stage?” 31.

[8] De Kosnik, “Is Twitter a Stage?” 27.

[9] De Kosnik, “Is Twitter a Stage?” 30.

[10] Crisitina Albu, “Mirror Affect: Interpersonal Spectatorship in Installation Art Since the 1960s,” (Doctorial thesis, University of Pittsburgh, 2012,) 33.